By Mark J. Price Akron Beacon Journal

Published December 31, 2007

After months of bitter debate and loud protest, the end came quietly on New Year’s Eve. Assistant Akron Law Director Alva J. Russell submitted a final transcript of annexation proceedings. Summit County Recorder Mary Paul stamped the official document.

Kenmore officially ceased to exist at 6 p.m. Dec. 31, 1928. Overnight, its 18,000 residents transformed into Akron citizens. Some of them went reluctantly.

Once hailed as “the fastest-growing city in the world,” Kenmore lasted a mere 20 years as a municipality. Those were 20 memorable years, however.

The Akron Realty Co. carved the town out of Coventry Township pastures and cornfields in the early 1900s. Kenmore’s chief backers were Noah R. Steiner, president of Akron Realty; William A. Johnston, manager of the Barberton Land and Improvement Co.; and Will Christy, president of the Northern Ohio Traction Co.

The men envisioned a residential area between Akron and Barberton with a streetcar line connecting the two thriving communities.

The crowning feature would be a 100-foot-wide boulevard passing through the center of the town. Double tracks would run down the middle.

“In Kenmore, there will be five-foot grass plats on either side of the tracks, and the trolley poles will be placed in the ‘devil’ strip between the two tracks,” the Beacon Journal reported in 1901. “Neat metal stations will be placed at frequent intervals along the boulevard. The trolley poles will be painted white. Every 600 feet along the entire length of the boulevard there will be placed an electric arc light, thus lighting the entire boulevard.”

Steiner wanted to name the town Hazelhurst or Hazeldale in honor of his daughter Hazel Steiner, the future Mrs. Bert A. Polsky. For reasons still unclear, he decided to call it Kenmore. Local historians have disagreed on whether the name derives from a place in New York, New Jersey, Virginia or England.

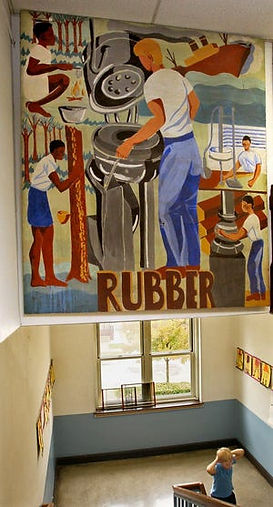

Developers touted Kenmore as a nice neighborhood far away from the smoke and dust of factories. Its lots were mostly residential, although a few notable companies — such as Diamond Rubber Co., Colonial Salt, Zimmerly Bros. Packing Co. and Webster, Camp & Lane — lurked on the outskirts of town.

Akron Realty sold 1,500 lots in 1901 for “the new town whose brilliant future is already assured.” Dozens of dwellings, churches and other buildings rose on tree-lined Kenmore Boulevard. Real-estate dealer M.C. Heminger was the first to move his family to the boulevard.

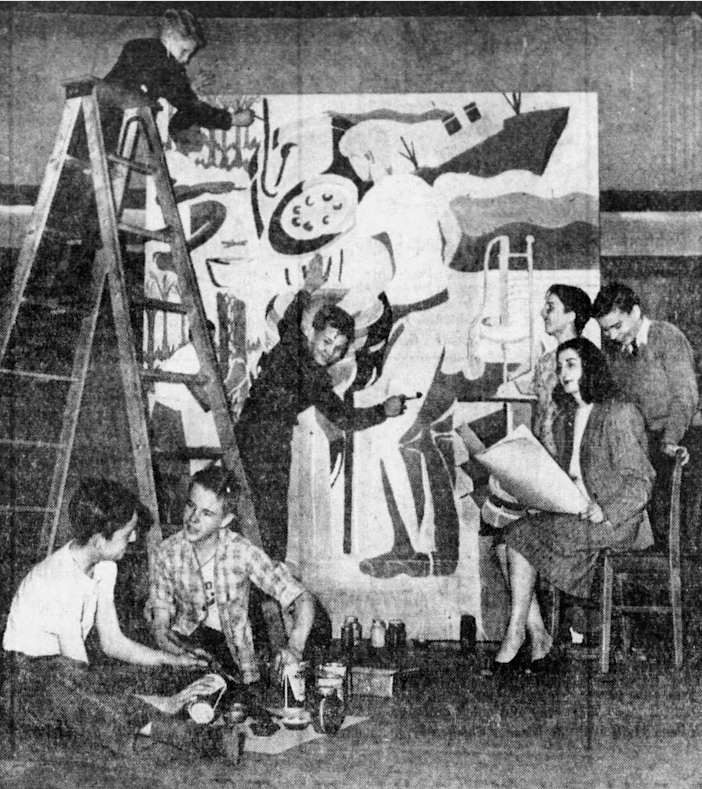

Kenmore schools began in 1903. The high school’s first graduating class in 1907 consisted of four students — Elsie Wagoner, Floyd Wagoner, Vesta Heminger and Maggie Henry.

The little town kept growing. On Dec. 28, 1907, Kenmore residents voted 77-11 to incorporate into a village. Incorporation papers were filed Jan. 9, 1908, and the change took effect in February.

Voters went to the polls that March to choose Kenmore’s first leaders. Elected were Mayor Charles Smith, Treasurer Byron W. Swigart and City Council members John Bergdorf, Orion D. Capron, Blanchard McFarlin, George W. Foust, Madison C. Lotz and Jacob Wirth.

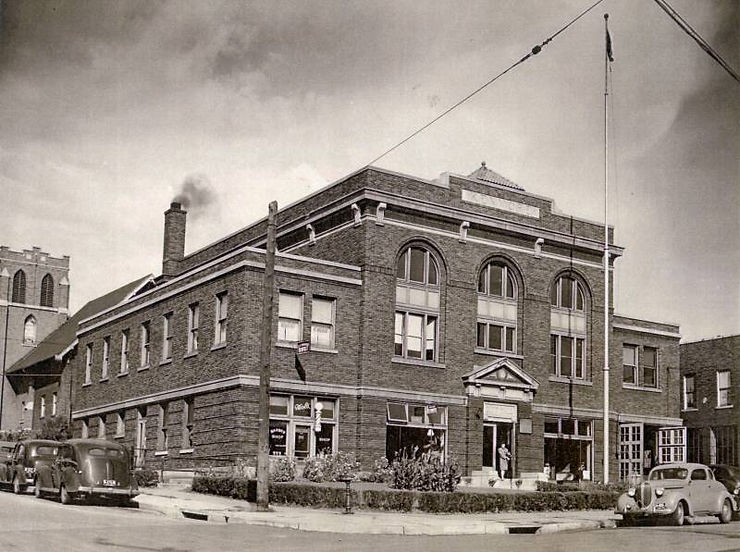

Officials met at Central School until Kenmore City Hall, a handsome brick building, opened in 1916.

“That the mayor and councilmen are serving without salary in spite of the fact that much of their time is devoted to the interest of the village shows the spirit actuating them,” the Beacon Journal reported. “It is safe to predict that within a year or two, Kenmore will be a model little village, both as to government and dress.”

Little village? Its population exploded 300 percent over the next decade to 18,000.

The bustling community earned the nickname as “the fastest-growing city in the world.” Its famous boulevard was a blur of activity as citizens went about their daily lives.

Such rapid growth proved to be Kenmore’s undoing. The city was 90 percent residential and had few industries from which to collect taxes. When the city fell into debt, it couldn’t provide adequate public services.

So it charged residents more.

The breaking point came in 1928, when the Kenmore City Council approved an ordinance that increased sewer bills $8 a year. Angry citizens formed a committee to explore the city’s possible annexation to Akron, which could provide better services at lower cost.

Former Kenmore Councilman Henry G. Morris led the campaign.

“In comparison with other cities of similar size, important public services, such as garbage collection, street cleaning, health control, public library and provision for care of indigent persons have been either nonexistent or developed in a manner having little appeal to the people on account of the added assessments created and poor service offered,” he wrote.

The revolt caused a bitter divide in the community. Accusations flew. Neighbors turned against neighbors.

Four Kenmore councilmen were jailed for a week in contempt of court when they resigned office rather than place the merger before voters.

Finally, the issue made it to the November 1928 ballot in Akron and Kenmore. It had to pass in both cities to take effect.

Akron overwhelmingly approved it, 59,010 to 11,618. Kenmore was more cautious, but still voted 3,854 to 2,225 in favor.

The merger of the two cities wiped Kenmore off the map — beginning with addresses. Many Kenmore streets had been named for U.S. states. They were changed to numbered avenues to avoid duplication with Akron streets.

The Kenmore Herald, founded in 1913, ceased operations.

Kenmore City Hall ended its governmental duties. Most Kenmore officials lost their jobs, although Police Chief William Poalson and his six officers joined the Akron force while Fire Chief Fred Kelly and his three firefighters joined the Akron squad.

The city’s demise was a mere formality when the annexation document arrived at the recorder’s office on New Year’s Eve. With the official’s stamp, Kenmore became the 9th and 10th wards of Akron.

Kenmore lost its city status but it didn’t lose its identity. To this day, it remains a tightknit community with deep civic pride. The streetcars are gone, but Kenmore Boulevard continues to be the center of activity.

The Akron Realty Co. picked the right location in 1901 when it began laying out a town — “For the investor and the man or woman who wishes to create a competency for later years, there is no spot or place where a few dollars will show greater earnings than purchases made in Kenmore.

“For as sure as the sun rises in the east, as if by magic, Kenmore will join the bounds of Akron with her sister city Barberton.”

Mark J. Price can be reached at mprice@thebeaconjournal.com.